Table of Contents

Introduction

Mahavira (Sanskrit: ), also known as Vardhamana, was Jainism’s 24th Tirthankara. He was the spiritual heir of Parshvanatha, the 23rd Tirthankara. In the early sixth century BCE, Mahavira was born into a noble Jain family in Bihar, India. Trishala was his mother’s name, and Siddhartha was his father’s. They were Parshvanatha’s lay devotees. At roughly 30, Mahavira gave up all of his worldly goods and left home in search of spiritual awakening, becoming an ascetic. Mahavira obtained Kevala Gyan after twelve and a half years of intensive meditation and severe austerities (omniscience). He preached for 30 years and obtained Moksha (freedom) in the 6th century BCE; however, the exact year varies depending on the sect.

Mahavira was an older contemporary of Gautama Buddha, who advocated Jainism in ancient India. Mahavira taught that spiritual emancipation requires observation of the vows of ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truth), asteya (non-stealing), brahmacharya (chastity), and aparigraha (non-attachment). He taught the syadvada and nayavada principles of Anekantavada (many-sided reality). Indrabhuti Gautama (his principal pupil) codified Mahavira’s teachings as the Jain Agamas. The scriptures, which were passed down orally by Jain monks, are thought to have been lost by the 1st century CE (when the remaining were first written down in the Svetambara tradition). The surviving forms of Mahavira’s Agamas are among the foundation texts of Svetambara Jainism. However, their legitimacy is questioned in Digambara Jainism.

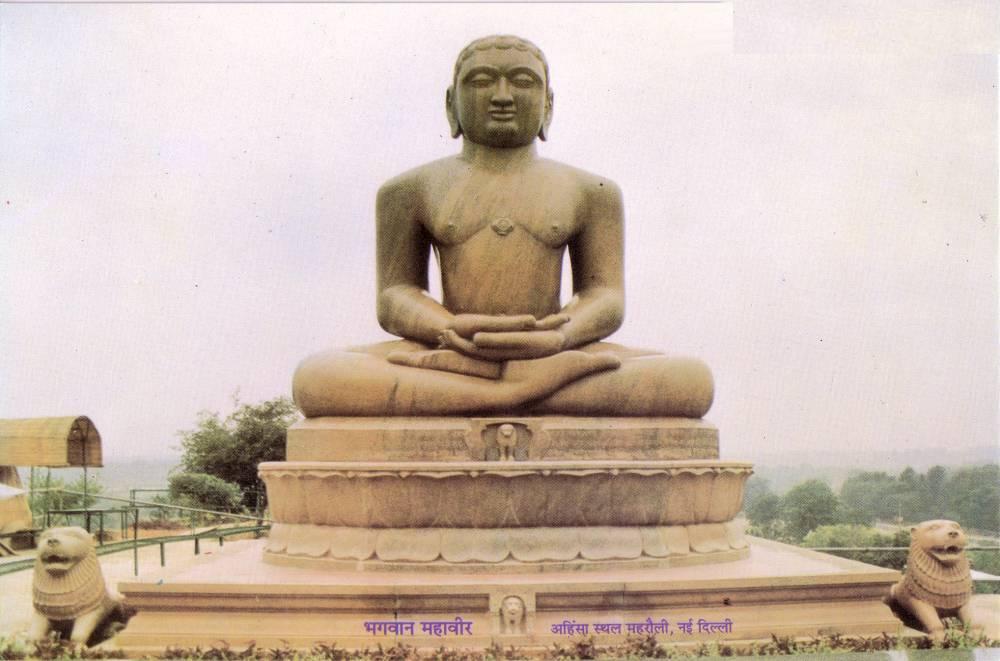

Mahavira is frequently represented in a meditative pose, seated or standing, with a lion emblem beneath him. His earliest iconography dates from the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE and comes from archaeological sites in the North Indian city of Mathura. Shri Gautama Swami’s birth is commemorated as Mahavir Janma Kalyanak, while his nirvana (salvation) and first shishya (spiritual illumination) are celebrated as Diwali.

Birth and Early Life of Lord Mahavira

Tirthankara Mahavira was born into the royal Kshatriya family of Ikshvaku Dynasty King Siddhartha and Licchavi Dynasty Queen Trishala. Rishabhanatha, the First Tirthankara, founded the Ikshvaku Dynasty. Mahavira was born in 599 BCE, according to Jains. In the Vira Nirvana Samvat calendar era, his birthday is on the thirteenth day of the rising moon in the month of Chaitra. It is known as Mahavir Janma Kalyanak by Jains and occurs in March or April on the Gregorian calendar.

The birthplace of Mahavira, Kundagrama, is thought to be near Vaishali, an old settlement in the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Its current position in Bihar is unknown, owing to migrations from ancient Bihar for economic and political reasons. Mahavira had several rebirths (totaling 27) before his 6th-century birth, according to Jain writings’ “Universal History.” Just before his last incarnation as the 24th Tirthankara, he encountered a demon, a lion, and a god (deva) in a heavenly world. According to the Svetambara traditions, his foetus was initially produced in the womb of a Brahman woman before being transferred to Trishala, Siddhartha’s wife, by Hari-Naigamesin (the heavenly leader of Indra’s army). The Digambara tradition does not believe in the embryo-transfer fable.

After Mahavira was born, the God Indra appeared from the sky with 56 dignitaries, anointed him, and performed his abhisheka (consecration) on Mount Meru. These events, shown in several Jain temples, are still used in present Jain temple rites. Although Svetambara Jains repeat the Kalpa Stra narratives of Mahavira’s birth tales during the yearly Paryushana festival, the Digambaras observe the same holiday sans the recital. Mahavira was a royal as a child. His parents were lay disciples of Parshvanatha, according to the second chapter of the vtmbara Acharanga Sutra. Mahavira may or may not have married, according to Jain tradition. His parents wanted him to marry Yashoda, according to Digambara tradition, but he was rejected. According to vtmbara tradition, he married Yashoda while young and had one daughter, Priyadarshana, also known as Anojja.

Mahavira is shown as tall in Jain writings; in the Aupapatika Sutra, his height is four cubits (6 feet). According to Jain literature, he was the shortest of the twenty-four Tirthankaras; prior teachers were said to have been taller, with Neminatha or Aristanemi, the 22nd Tirthankara, claimed to have been 65 cubits (98 feet) tall.

Teachings of Lord Mahavira

The following are the cardinal principles of Jainism:

1. Ahimsa (non-violence)

2. Anekantvada (multiplicity of views)

3. Aparigraha (non-possessiveness)

4. Non-stealing

5. Brahmacharya

The first and third are relatively straightforward, while the second requires some explanation. Jain literature is discussed under the heading ‘Multiplicity of Viewpoints and Relativism (Syadavada).’ Different points of view frequently add to the information, and one should infer only after hearing various perspectives on a subject. If this isn’t done, the conclusions drawn may be skewed or erroneous. It ensures that others’ points of view are tolerated. Only after hearing others may one have a better perception. The story of the eight blind men and the elephant, for example, is well-known. Although each of the blind men’s opinions about the elephant were valid, each view could only provide a partial picture of the situation. Only by listening to all of them could one have a complete understanding of elephants.

On occasion, an object can be described by two entirely opposing statements: it is (ASTI), and it is not (ASTI) (NASTI). These two statements can be applied to any of the following: (1) substance, (2) location, (3) time, and (4) form. Let’s use a piece of furniture as an example. Furniture constructed of jungle wood is not the same as furniture made of sandalwood. It could also be found in a particular room but not in others. As a result, it can be stated in two ways that appear to be opposed. ASTI – NASTI – VADA is the acronym for this method of specification.

Another set of logic lines constructed by Jain philosophers postulates that there can be up to seven modes of prediction in every given scenario. This teaches the concept of probability by introducing an element of uncertainty into the forecasts. The doctrine of’may be’ is known as Syadavada. When we look at both the Jainist and Vedantic ideologies, we can see that they are both true in their way. They are not in conflict with one another. Because the Jain philosophy does not delve as deeply into the process of creation as Vedantism, it (Vedantism) concludes with The God as the First Cause. On the other hand, Jainism presents the Syadavada, a beautiful notion of accommodation required for the accurate judgment of anything to help familiar humans understand the complexity of the universe. Because Jainism defines life in practically every way, it advocates a high level of non-violence.

Every element, according to Mahavira, was a blend of secular and spiritual forces. While the material aspect is transient, the spiritual factor is permanent and continues to evolve. He believed that karma held the soul in a state of servitude. Getting rid of desires helps free the soul from its shackles. Only the breakdown of the Karmik energy, he felt, could fully liberate the soul. According to him, the intrinsic value of the soul can be accentuated when the karmas diminish, and the soul can shine brightly. When the soul achieves infinite greatness, it transforms into Paramatma, the pure soul, who possesses limitless knowledge, power, and bliss.

According to Mahavira, the primary goal of life is to achieve salvation. As a result, he insisted on avoiding evil Karmas, preventing all types of new Karmas, and destroying those that already existed. According to him, non-injury (Ahimsa), speaking the truth (Satya), non-stealing (Asteya), non-adultery (Brahmacharya), and non-possession are the five vows that can be fulfilled (aparigraha). He insisted on principles of proper conduct, good faith, and correct knowledge in addition to these five vows. Appropriate behavior implied a detached attitude toward the senses. He stated that we should consider hardship and enjoyment on an equal footing. Good faith meant believing in the Jinas, and proper knowledge meant knowing when the Jinas would be freed. The vows and principles listed above were intended for the householders. The Monks, for example, had to adhere to a stricter code.

Mahavira did not believe in God, nor did he believe that He created or controlled the universe in any way. According to him, the world will never end. No matter comes to an end; it merely takes on a new form. Because the cosmos is made up of particular materials, it simply changes its shape. In terms of this principle, we can see the influence of Sankhya’s philosophy. Mahavira also felt that man’s survival did not rely on the mercy of any external authority. The individual was in charge of his fate. Man can get rid of his afflictions and sorrows by living a life of austerity and self-mortification. Mahavira believes that the only road to salvation is via renunciation. The Vedic idea was also rejected by Jainism, as were the Brahmans’ sacrifice rites.

Mahavira gave ahimsa far too much weight. All things, animals, plants, stones, and rocks, according to him, have life, and one should not damage another invoice, deed, or action. Though this philosophy was not wholly new, the Jains are credited with popularizing it and thus putting an end to various types of sacrifices. The above teachings of Mahavira demonstrate that he was more of a reformer of an existing religion than a founder of a new faith.

Final Note

In conclusion, the Jains regard Tirthankara as the most excellent ideal, possessing complete knowledge, endless happiness, and boundless power. This happy feeling reminds me of the Vedantic ‘Chitananda.’ Arhat and Siddha are Jainism’s equivalents to Vedantic Jivan Mukta (free from existence) and Videha Mukta (free from suffering) ( free from body ). As in the case of King Janaka, a Jivan Mukta could also be a Videha Mukta. Tirthankaras are Siddhas who, throughout their lifetime, profound the truth, which is a higher thing. Arhats, Siddhas, and Tirthankaras are Jains who, in simpler terms and in the same way, are those who merit, accomplish, and sanctify. Every man can reach the maximum level. In Jain philosophy, Tirthankaras assume the place of God.

“Jainism is thus more of a moral code than a religion in the modern western sense.” It had no concept of a Supreme Being, but it did recognize a galaxy of deified men who had achieved spiritual greatness. Every soul could be as magnificent as they were. If the need arose, Jainism was not opposed to welcoming a God from popular Hinduism into our cosmos. Furthermore, it was not opposed to the caste theory. As a result, it was far less hostile to Hinduism and far more accepting than the other heterodox systems. It’s also worth remembering that Jainism was not a dogmatic religion. There could be no absolute affirmation or denial, according to its reasoning. When all knowledge is simply speculative and relative, your opponent’s point of view is just as likely as yours to be correct. As a result of this attitude of compromise, Jainism has remained in India to this day, while Buddhism, its twin sister, has had to seek refuge elsewhere.”

Mahavir made religion natural and straightforward, devoid of complicated rituals. His teachings mirrored the soul’s inner beauty and harmony. Mahavir preached the idea of human life’s superiority and emphasized the significance of a positive outlook on life. Mahavir’s non-violence (Ahimsa), truth (Satya), non-stealing (Acharya), celibacy (Brahmacharya), and non-possession (Aparigraha) messages are filled with universal compassion. “A living body is not only an integration of limbs and flesh,” Mahavir explained, “but it is the home of the soul, capable of perfect perception (Anant darshana), perfect knowledge (Anant jnana), perfect strength (Anant virya), and perfect pleasure” (Anant sukha). Mahavir’s teaching portrays the living being’s independence and spiritual bliss. Mahavir emphasized that all living beings are equal, regardless of their size, shape, or form, or their spiritual development or lack thereof, and that we should love and respect them. He proclaimed the message of global love in this manner. Mahavir rejected the idea of God as the universe’s creator, defender, and destroyer. He also condemned the worship of gods and goddesses to gain financial wealth and personal gain. A lot of people have faith in Lord Mahavira’s teachings and beliefs and because of this he is a world known person.