Table of Contents

Vedas

The Vedas (/vedz/, IAST: Veda, Sanskrit: lit. ‘Knowledge’) is a collection of religious books from ancient India. The books, written in Vedic Sanskrit, are the earliest layer of Sanskrit literature and Hinduism’s oldest scriptures. The Yajurveda, the Rigveda, the Samaveda, and the Atharvaveda are the four Vedas. The Aranyakas (text on rituals, gifts, sacrifices, and symbolic-sacrifices), the Brahmanas (commentaries on rituals, traditions, and skills), the Upanishads (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies, and gifts), and Samhitas (mantras and benedictions) are the four subdivisions of each Veda (texts discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge). The Upasanas, according to specific experts, is a fifth category (worship). The Upanishads’ texts explore themes that are similar to the heterodox sramana-traditions.

The Vedas are named ruti (“what is heard”), in contrast to other religious books, which are called smiti (“what is remembered”). The Vedas are considered apadravya, which means “not of a man, superhuman” and “impersonal, authorless” revelations of sacred sounds and texts heard by ancient sages after intense meditation, according to Hindus. The Vedas have been spread from one person to another orally from the second millennium BCE, using complex mnemonic procedures. The earliest Vedas, the mantras, are chanted for their phonology rather than their semantics in modern times. They are said to be “primordial rhythms of creation,” occurring before the forms they allude to. The cosmos is rejuvenated by repeating them, “by enlivening and sustaining the forms of creation at their root.”

The Vedas have been interpreted differently by various Indian philosophies and Hindu religions; schools of Indian philosophy that recognize the Vedas’ fundamental authority are described as “orthodox” (stika). Other ramaa traditions that did not view the Vedas as authoritative, such as Lokayata, Carvaka, Ajivika, Buddhism, and Jainism, are referred to as “heterodox” or “non-orthodox” (nastika) schools.

Vedas: Usage and Etymology

The Sanskrit term véda, which means “knowledge, wisdom,” comes from the root vid-, which means “to know.” This thought came from the Proto-Indo-European root *ueid-, which means “to see” or “to know.” The word is derived from Proto-Indo-European *ueidos, which is cognate with Greek ()o “aspect” and “shape.” This should not be confused with the eponymous 1st and 3rd person singular perfect tense véda, which is connected with Greek () (w)oida “I know.” Greek, English wit, etc., Latin vide “I see,” German Wissen “to know,” etc., are root cognates.

Veda is a widespread noun in Sanskrit that signifies “knowledge.” In some instances, such as the Rigvedic hymn 10.93.11, the phrase indicates “obtaining or discovering money, property,” but in others, it means “a cluster of grass together,” as in a broom or for a ritual fire.

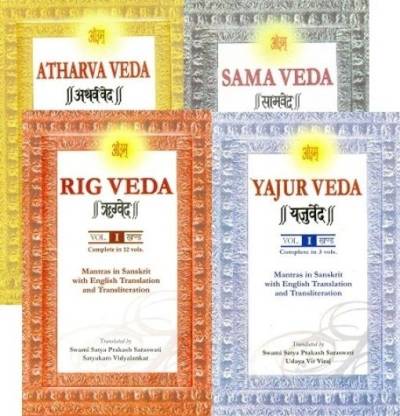

The Four Vedas

The Vedas are divided into four categories (turya): Rigveda (RV), Yajurveda (YV, with the central division TS vs. VS), Samaveda (SV), and Atharvaveda (AV) (AV). The first three were the initial divisions, commonly known as “tray vidy,” or “the triple science” of reciting hymns (Rigveda), conducting sacrifices (Yajurveda), and chanting songs (Yajurveda) (Samaveda). The Rig Veda was most likely written between 1500 and 1200 BC. The Vedic period, according to Witzel, is when incipient lists divide the Vedic writings into three (tray) or four branches: Rig, Yajur, Sama, and Atharva.

The Samhitas (mantras, benedictions), the Aranyakas (text on ceremonies such as newborn baby’s rites of passage, coming of age, marriages, retirement and funeral, sacrifices and symbolic sacrifices), the Brahmanas (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies, and sacrifices), and the Upanishads (commentaries on rituals, traditions, and sacrifices) are the four major text types found in each Veda (text discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge). Some academics believe the Upasanas (short ritual worship-related parts) to be the fifth part. According to Witzel, the rituals, rites, and ceremonies recorded in these ancient documents reproduce Indo-European marriage customs witnessed in a territory encompassing the Indian subcontinent, Persia, and Europe, with some more essential details found in Vedic era texts like the Grhya Stars. Only one Rigveda version is known to have survived to the present day. Numerous different versions of the Sama Veda and the Atharva Veda have been discovered in various locations of South Asia, as have many different versions of the Yajur Veda. The Upanishads’ texts explore themes that are similar to the heterodox sramana-traditions.

Rigveda

The oldest existing Indic text is the Rigveda Samhita. It consists of ten books with 1,028 Vedic Sanskrit hymns and 10,600 verses (Sanskrit: mandalas). The hymns pay homage to Rigvedic gods. The volumes were written over several centuries in Punjab (Sapta Sindhu) region of the northwest Indian subcontinent by poets from various priestly groups between c. 1500 and 1200 BC (the early Vedic period). According to Michael Witzel, the Rigveda was first codified in the early Kuru dynasty near the Rigvedic period, around 1200 BCE. The Rigveda is organized around a set of principles. The Veda begins with a bit of book dedicated to Agni, Indra, Soma, and other gods, all of whom are listed in order of decreasing a total number of hymns in each deity collection; songs are shorter as the deity series progresses, but the number of accolades each book grows. Finally, as the text develops, the meter is systematically organized from jagati and tristubh to anustubh and Gayatri.

The ceremonies grew more intricate over time, and the king’s participation bolstered both the Brahmans’ and the kings’ positions. “Set in movement cyclical regenerations of the universe,” according to the Rajasuya ceremonies, which are performed in conjunction with a king’s coronation. In terms of content, hymns transition from early works’ praise of deities to Nasadiya Sukta’s hymns, which address themes such as “what is the foundation of the universe?” and “do even gods know the answer?” as well as the virtue of Dna (charity) in society and other philosophical topics. The mythology, rites, and linguistics of the Rigveda are identical to those of ancient Central Asia, Iran, and the Hindukush (Afghanistan) regions.

Samaveda

The Samaveda Samhita is 1549 stanzas derived almost entirely from the Rigveda (save for 75 mantras). While its earliest elements are thought to date from the Rigvedic period, the current collection dates from the post-Rigvedic Mantra phase of Vedic Sanskrit, roughly contemporaneous with the Atharvaveda and the Yajurveda, between c. 1200 and 1000 BCE or “slightly later.”

The Samaveda Samhita is divided into two sections. The first section contains four music collections (GNA,) and the second section includes three verse “books” (rcika,). A verse in the arcika books corresponds to a tune in the songbooks. The early areas of the Samaveda, like the Rigveda, often begin with hymns to Agni and Indra before shifting to the abstract. Their meters move in a downward order as well. The hymns taken from Samaveda’s later sections have the slightest variation from the melodies produced from Rigveda’s earlier sections. Some Rigvedic passages are repeated in the Samaveda. There are in total 1875 verses numbered in Griffith’s Samaveda recension, including repetitions. The Kauthuma/Ranayaniya and the Jaiminiya recensions have survived. Its aim was liturgical, part of the budget or “singer” priests’ repertoire.

Yajurveda

Prose mantras make up the Yajurveda Samhita. It is a collection of ritual offering mantras recited by a priest as a person conducted ritual tasks such as those performed before the yajna fire. The Yajurveda’s core text dates from the end of the second millennium BCE, making it younger than the Rigveda and roughly contemporaneous with the Atharvaveda, Rigvedic Khilani, and Samaveda. According to Witzel, the Yajurveda hymns are dated to the early Indian Iron Age, between c. 1200 and 800 BCE, corresponding to the early Kuru kingdom. The earliest and oldest stratum of the Yajurveda Samhita has approximately 1,875 poems that are unique but borrow and build on the foundation of Rigvedic verses. Unlike the Samaveda, which is nearly exclusively composed of Rigveda mantras and organized as songs, the Yajurveda Samhitas are written in prose and are linguistically distinct from previous Vedic writings. The Yajur Veda has long served as the principal source of knowledge about Vedic sacrifices and accompanying ceremonies.

In this Veda, there are two primary groups of texts: the “Black” (Krishna) and the “White” (Vishnu) (Shukla). Contrary to the “white” (well arranged) Yajurveda, the term “black” refers to the “un-arranged, motley assemblage” of poems in Yajurveda. The Samhita is separated from its Brahmana (the Shatapatha Brahmana) in the White Yajurveda, while the Black Yajurveda intersperses the Samhita with Brahmana commentary. Texts from four primary schools of the Black Yajurveda have survived (Maitrayani, Katha, Kapisthala-Katha, Taittiriya), while two primary schools of the White Yajurveda have survived (Maitrayani, Katha, Kapisthala-Katha, Taittiriya) (Kanva and Madhyandina). The newest layer of Yajurveda text has little to do with sacrifices or rituals. Still, it does contain the most extensive collection of basic Upanishads, which have influenced numerous schools of Hindu thought.

Atharvaveda

The text of the Atharvan and Angirasa poets’ is known as the Atharvaveda Samhita. It has roughly 760 hymns, with about 160 of them being shared with the Rigveda. The majority of the verses are metrical, although a few passages are written in prose. The Paippalda and the aunakya are two separate versions of the text that have survived into modern times. In the Vedic age, the Atharvaveda was not recognized as a Veda, but it was accepted as a Veda in the late 1st millennium BCE. It was the latest to be written, presumably around 900 BCE; however, some of the material may date back to the Rigveda’s time or before. The Atharvaveda is frequently referred to as the “Veda of magical formulas,” a moniker disputed by some researchers. The Samhita layer of the book most likely depicts a burgeoning 2nd millennium BCE tradition of magico-religious rites to alleviate superstitious worry, spells to eliminate ailments believed to be caused by demons, and medicine made from plants and nature. According to Kenneth Zysk, the text is one of the oldest surviving records of religious medicine’s evolutionary practices, revealing the “earliest kinds of folk healing of Indo-European antiquity.” Many of Atharvaveda Samhita’s books are devoted to non-magical rites, such as philosophical thoughts and theosophy.

The Atharva Veda has long served as the primary source of information on Vedic culture, customs and beliefs, goals and frustrations in everyday Vedic life, and kings and governance. Hymns dealing with the two primary rites of passage — marriage, and cremation – are also included in the text. The Atharva Veda devotes a large section of its text to elucidating the meaning of a ceremony.

Vedic Texts

The phrase “Vedic texts” has two different connotations: During the Vedic period, texts were written in Vedic Sanskrit (Iron Age India). Any text is considered a “corollary of the Vedas” or “related to the Vedas.” The Vedic Sanskrit corpus comprises the following texts: The Samhitas (Sanskrit sahit, “collection”) are metric text collections (“mantras”). The Rig-Veda, Yajur-Veda, Sama-Veda, and Atharva-Veda are the four “Vedic” Samhitas available in multiple recensions (kh). The word Veda is often used exclusively to refer to these Samhitas or collections of mantras. This is the oldest stratum of Vedic literature, written between 1500 and 1200 BCE (Rig Veda books 2–9) and 1200 to 900 BCE (other Samhitas). Invocations to deities like Indra and Agni are found in the Samhitas, and they are said to be made “to win their benediction for victory in battles or for the prosperity of the clan.” According to Bloomfield’s Vedic Concordance (1907), the total corpus of Vedic mantras is 89,000 padas (metrical feet), of which 72,000 are found in the four Samhitas.

The texts deemed “Vedic” in the sense of “corollaries of the Vedas” are less precisely defined and may include various post-Vedic books such as later Upanishads and Smriti texts Shrauta Sutras and Gryha Sutras. The Vedas and these Sutras make up the Vedic Sanskrit corpus as a whole. While the production of Brahmanas and Aranyakas came to a stop with the end of the Vedic period, new Upanishads were written after that. The Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads, for example, interpret and discuss the Samhitas in philosophical and symbolic ways to investigate abstract notions like the Absolute (Brahman) and the soul or self (Atman), establishing Vedanta philosophy, one of later Hinduism’s critical tendencies. They also show the evolution of ideas in the Upanishads, from actual sacrifice to symbolic sacrifice and spirituality. Later, Hindu academics, such as Adi Shankara, divided the Vedas into karma-Kanda (action/sacrificial ritual-related sections, such as the Samhitas and Brahmanas) and jnana-Kanda (knowledge/spirituality-related sections, like the Upanishads).

Smriti and Sruti

The Vedas are named ruti (“what is heard”), as opposed to smti (“other religious texts”) (“what is remembered”). Max Müller accepted this indigenous categorization method, and while it is controversial, it is still commonly used. These classifications are frequently untenable for linguistic and formal reasons, as Axel Michaels explains: At any given time, there are several collections handed down in separate Vedic schools; Upanişads […] are sometimes difficult to distinguish from rayakas […]; Brhmaas contain older strata of language attributed to the Sahits; the Vedic schools have various dialects and locally prominent traditions. Nonetheless, it is best to stay to Max Müller’s division because it maintains Indian practice, accurately represents the chronological order and underpins modern Vedic literature editions, translations, and monographs.

Authorship

Hindus consider the Vedas apadravya, which means “not of man, superhuman” and “impersonal, authorless.” The Vedas are considered revelations witnessed by ancient sages after intense concentration by orthodox Indian theologians and manuscripts that have been more carefully preserved from ancient times. Brahma is credited with creating the Vedas in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. The Vedic songs claim to have been masterfully crafted by Rishis (sages) following inspired inspiration, much like a carpenter crafts a chariot.

The oldest part of the Rigveda Samhita was orally composed in northwestern India (Punjab) between c. 1500 and 1200 BC,[note 1], while book 10 of the Rig Veda, as well as the other Samhitas, were written between 1200 and 900 BCE more eastward, between the Yamuna and the Ganges, the heartland of Aryavarta and the Kuru Kingdom (c. 1200 – c The “circum-Vedic” manuscripts and the Samhitas’ redaction date from around 1000–500 BCE. Vyasa is the creator and compiler of the Vedas, who divided the four types of mantras into four Samhitas (Collections).

Structure of the Vedas

Vedas, which means “knowledge,” was written in Vedic Sanskrit in the Indian Subcontinent’s northwestern region between 1500 and 500 BCE. The Vedas were passed down verbally for millennia before being written down. Because the focus is on the concepts found in Vedic tradition rather than those who produced the ideas, nothing is known about the Vedas’ authors. The Rig Veda is the oldest of the texts, and while the dates for each of the ancient books are impossible to determine, the collection is thought to have been completed by the end of the 2nd millennium BCE (Before Common Era).

The Rig Veda is the most crucial Vedic text, with 1,028 hymns organized into ten books known as mandalas. Although they are arranged differently to be recited, Sam Veda’s words are almost entirely copied from the Rig Veda. The White and Black portions of the Yajurveda offer written remarks on how rituals and sacrifices should be made. The Atharva Veda contains charms and magical incantations written in folklore style. The Brahmanas, instructions for religious ceremonies, and the Samhitas, mantras or poems in the worship of numerous deities, were separated into two divisions in each Veda. According to modern linguists, the metrical hymns of the Rigveda Samhita, the oldest layer of text in the Vedas, are thought to have been created by several authors throughout several centuries of oral tradition. Even though the Vedas place a greater emphasis on the message than on the messengers, such as Buddha or Jesus Christ in their respective religions, the Vedic religion nonetheless revered gods.

Teachings of the Vedas

Our knowledge is prone to several flaws in the conditioned state. A conditioned soul differs from a freed soul in that the conditioned soul contains four types of defects. The first flaw is that he is prone to making blunders. For example, Mahatma Gandhi was regarded as a tremendous personality, but he made numerous errors. “Mahatma Gandhi, don’t go to New Delhi conference,” his assistant cautioned him even at the end of his life. I have some acquaintances, and I’ve heard there’s a threat.” But he was deafeningly deafening. He persisted in going, and he was slain as a result. Even significant figures like Mahatma Gandhi and President John F. Kennedy, to name a few, make mistakes. Error is a natural part of life. This is one of the conditioned soul’s flaws.

Another flaw is the ability to deceive. Accepting something that isn’t true is called illusion: Maya. Maya denotes the absence of something. Everyone takes their bodies as their true selves. “I am Mr. John; I am a wealthy guy; I am this, I am that,” you’ll say if I ask what you are. All of them are physical identifiers. You, or for that matter, I, on the other hand, are not this body. This is a trick of the eye. The tendency to cheat is the third flaw. Everyone tends to deceive others. Even if a guy is the first fool, he presents himself as very intelligent. Even though he is in denial and makes mistakes, he will theorize: “I believe this is this, this is this.” He, on the other hand, has no clue where he stands. He is a philosopher who writes books despite his flaws. That is his affliction. That is unethical.

Finally, our senses are flawed. Our eyes are something we are incredibly proud of. “Can you show me God?” someone will often ask. Do you, on the other hand, have the sight to see God? If you don’t have eyes, you won’t be able to see anything. You won’t be able to see your hands if the room darkens quickly. So, what kind of idea do you have? As a result, we cannot expect wisdom (Veda) from our faulty senses. With all of these flaws, we cannot provide excellent knowledge to anyone in our conditioned lives. We aren’t flawless either. As a result, we embrace the Vedas in their current form.

The Vedas may be referred to as Hindu. However, Hindu is a foreign term. We aren’t Hindus by any stretch of the imagination. The term varnasrama refers to our true identity. Varnasrama refers to Vedic adherents who accept the division of human society into eight varnas and asramas. Society is divided into four categories, while spiritual life is divided into four categories. This is referred to as varnashrama. “These divides are everywhere because they are created by God,” the Bhagavad-gita says. Brahmana, ksatriya, vaisya, and sudra are the social divisions. Brahmana refers to a brilliant class of persons who understand what it means to be Brahman. The Kshatriyas, or administrators, are the second most intelligent group of individuals. The Vaisyas, or merchants, came next. Natural categories may be found all over the place. This is the Vedic principle, and it is one that we accept.

Because there can be no error, Vedic ideas are recognized as an axiomatic truth. That is what acceptance is all about. In India, for example, cow dung is considered pure, even though it is an animal’s excrement. The Vedic warning that if you touch stool, you must take a bath right away may be found in one place. However, it is stated that a cow’s feces is pure in another region. When you smear cow dung on an impure area, it becomes clear. “This is paradoxical,” we can say with our common sense. It is, in fact, paradoxical from a conventional standpoint, yet it is not wrong. It’s a fact. A well-known scientist and doctor in Calcutta examined cow dung and discovered that it possesses all antibacterial characteristics.

If someone says to another in India, “You must do this,” the other party may respond, “What do you mean?” Is this a Vedic command that I must follow you without question?” Injunctions in the Vedas cannot be deciphered. But, in the end, if you examine why these prohibitions exist, you will see that they are all valid. The Vedas aren’t a collection of human wisdom. Lord Krishna, the spiritual world’s source of Vedic wisdom. Sruti is another term for the Vedas. Sruti refers to the information gained via hearing. It isn’t knowledge gained via experimentation. Sruti is seen as a maternal figure.

Our mother instills in us a wealth of wisdom. Who can tell you who your father is, for example, if you don’t know who he is? Your mum, to be precise. You must accept your father if your mother says, “Here is your father.” It’s impossible to test to see if he’s your biological father.

Similarly, you must accept the Vedas if you want to know anything beyond your experience, experiential knowledge, and senses’ activity. Experimentation is not an option. It has already been tried out. It has already been decided. For example, the mother’s story must be recognized as accurate. There isn’t any other option. The Vedas are regarded as the mother, and Brahma is referred to as the grandfather or forefather because he was the first to be taught Vedic knowledge. Brahma was the first living entity in the universe. He obtained Vedic wisdom and passed it on to Narada and other disciples and sons, who passed it on to their followers. The Vedic knowledge is passed down through disciplic succession in this way.

The Bhagavad-gita also confirms that Vedic knowledge is understood in this way. If you experiment, you will arrive at the same conclusion, but you should accept it to save time. If you desire to know your father and respect your mother’s authority, you can get whatever she says without question. Pratyaksa, anumana, and sabda are the three types of evidence. Pratyaksa is a Sanskrit word that means “straight.” Because our senses aren’t flawless, direct proof isn’t handy. We view the sun every day, and while it looks to us as a bit of disc, it is far more significant than many planets. What is the worth of this observation? As a result, we must study books to comprehend the sun. As a result, firsthand experience isn’t flawless.

Then there’s inductive knowledge: the notion “It could be like this.” For example, Darwin’s hypothesis states that it may be this or that, not science. That is merely a suggestion, and it is far from ideal. However, if you get your information from reliable sources, that is ideal. You accept a program guide if it is sent to you by the radio station. You don’t have to deny it; you don’t have to experiment because it comes from reliable sources. Sabda-pramana is the Vedic term for knowledge. Sruti is another name for Sruti. This knowledge must be gained solely by aural perception, according to Sruti. According to the Vedas, we must hear from the authority to comprehend transcendental knowledge. The ability from beyond this universe is referred to as transcendental knowledge. Material knowledge exists within this realm, and metaphysical knowledge exists beyond it. How can we shift to the spiritual world if we can’t even get to the end of the universe? As a result, obtaining complete information is impossible.

A spiritual sky exists. Beyond manifestation and non-manifestation, there is another nature. But how can you know if there is an endless sky with eternal planets and inhabitants? All of this information is there, but how will you test it? This isn’t feasible. As a result, you must rely on the Vedas for guidance. This is referred to as Vedic wisdom. We accept knowledge from the ultimate authority, Krishna, in our Krishna awareness movement. Krishna is regarded as the highest authority by individuals of all social groups. I’m referring to the first of two types of transcendentalists. Mayavadi, a kind of transcendentalist, is known as an impersonal. They are known as Vedantists, and Sankaracarya leads them. There is also a group of transcendentalists known as Vaishnavas, including Ramanujacarya, Madhvacarya, and Visnusvami. Krishna is recognized as the Supreme Personality of Godhead by both the Sankara-sampradaya and the Vaishnava-sampradaya. Sankaracarya is thought to have been impersonal who preached impersonalism and impersonal Brahman, although he is a covered personalist. “Narayana, who is the Supreme Personality of Godhead, is beyond this cosmic manifestation,” he stated in his commentary on the Bhagavad-gita. “That Supreme Personality of Godhead, Narayana, is Krishna,” he verified again. He has come as Devaki and Vasudeva’s kid.” He specifically mentioned His father and mother’s names.

As a result, all transcendentalists recognize Krishna as the Supreme Personality of Godhead. There is no denying it. The Bhagavad-gita, which is directly from Krishna, is our source of knowledge in Krishna awareness. We chose to publish Bhagavad-gita As It Is because we believe Krishna’s words should be heard as they are. This is Vedic wisdom. We accept Vedic knowledge because it is clean. We embrace anything Krishna says. This is what Krishna awareness is all about. This saves a lot of time.

You save a lot of time if you accept the proper authority or source of knowledge. For example, there are two types of knowledge systems in the material world: inductive and deductive. You acknowledge that man is mortal based on deductive reasoning. Your father thinks the man is mortal, your sister says man is human, and everyone else believes a man is human–but you don’t test this theory. Man’s mortality is something you accept as fact. If you want to find out if a man is mortal, you must study every individual. You may come to believe that some man is not dying, but you have yet to see him. As a result, your research will never be completed in this manner. The ascending process is referred to as Aroha in Sanskrit. You will never arrive at the correct conclusions if you seek knowledge by exercising your faulty senses through any personal initiative. This isn’t feasible. In the Brahma-Samhita, a line says, “Just ride on the aeroplane that travels at the speed of thought.” Our material planes can travel at speeds of up to 2,000 miles per hour, but what is the speed of thought? You’re sitting at home, and you think of India, which is 10,000 miles distant, and it suddenly appears in your home. Your thoughts have wandered there. The mind moves at such a fast pace. “If you move at this speed for millions of years, you’ll discover that the spiritual sky is boundless,” it is said. It’s impossible even to approach it.

As a result, the Vedic precept is to approach a genuine spiritual master, a guru–the word “compulsory” is employed. And what is a spiritual master’s qualification? He received the Vedic word from the correct source. He isn’t genuine if he isn’t. He needs to be practically entrenched in Brahman. The two attributes are as follows: This Krishna awareness movement is based on Vedic ideas and is entirely legal.

“The actual objective of Vedic research is to find out Krishna,” Krishna declares in the Bhagavad-gita. “Krishna, Govinda, has numerous forms, but they are all one,” according to Brahma-Samhita. They aren’t like our forms, which are subject to error. His physical form is impregnable. My form has a beginning, whereas His shape has not. It’s called Ananta. And His multiforms – there are so many of them — have no end. My application is here, not in my residence. You’re not in your place, but you’re sitting there. Krishna, on the other hand, can be everywhere at any moment. He can sit in Goloka Vrndavana and be everywhere, all-pervading at the same time. He is the first and oldest, but anytime you see a picture of Krishna, you will see a young boy between fifteen and twenty. You will never come across an older adult. Krishna as a charioteer has been depicted in the Bhagavad-gita. He was at least a hundred years old at the time. He had great-grandchildren, but he still had the appearance of a boy. Krishna, the Supreme Personality of God, never grows old. That is the extent of His power. And if you try to find Krishna by studying Vedic literature, you would be perplexed. It’s conceivable, but it’s complicated. However, you can readily learn about Him from one of His devotees. “Here He is, take Him,” one of His devotees can say. Krishna’s disciples have that kind of power.

There was just one Veda at first, and it was unnecessary to read it. People were so sharp and had clear memories that they could understand by hearing the spiritual master’s words. They’d get the gist of what was going on right away. However, Vyasadeva set the Vedas in writing for the people of this period, the Kali-yuga, 5,000 years ago. He recognized that the humans would eventually be short-lived, that their memories would be poor, and that their brains would be lacking. “As a result, allow me to write down this Vedic wisdom.” Rig, Sama, Atharva, and Yajur are the four Vedas he split. After that, Jesus entrusted these Vedas to his many followers. He then considered the lower classes of men, the stri, sudra, and Bandhu. He took into account the woman class, the sudra class (working class), and the dvija-Bandhu. Dvija-Bandhu refers to those who are born into wealthy families but lack the necessary qualifications. Dvija-Bandhu refers to a man born into a brahmana household but is not competent to be a brahmana. He wrote Mahabharata, also known as India’s history, and the eighteen Puranas for these people. The Puranas, the Mahabharata, the four Vedas, and the Upanisads are all Vedic kinds of literature. The Vedas include the Upanisads.

Then, in the Vedanta-sutra, Vyas deva collected all Vedic knowledge for intellectuals and philosophers. This is the Vedas’ final word. Vyas deva wrote Vedanta-sutra himself, following the directions of Narada, his spiritual master, and guru-maharaja, yet he was unsatisfied. The Srimad-Bhagavatam tells a long account about this. Even after compiling several Puranas, Upanisads, and the Vedanta-sutra, Vedavyasa felt unsatisfied. Then Narada, his spiritual instructor, told him, “You explain Vedanta.” Vedanta is “ultimate knowledge,” and Krishna is the ultimate knowledge.

Baladeva Vidyabhusana’s Govinda-bhasya is our Gaudiya Vaishnava exposition on Vedanta philosophy. Similarly, Ramanujacarya and Madhvacarya each have a commentary. The commentary of Sankaracarya is not the only one. Although there are many Vedanta comments, people mistakenly believe that Sankaracarya’s is the only Vedanta commentary since the Vaisnavas did not give the first Vedanta commentary. Aside from that, Vyasadeva wrote Srimad-Bhagavatam, the ultimate Vedanta commentary.

The Vedanta-first sutra’s words are likewise found in Srimad-Bhagavatam: janmady asya yatah. And the Srimad-Bhagavatam explains janmady asya yatah in detail. “The one absolute truth is that from whom everything emanates,” says the Vedanta-sutra, implying what is Brahman, the Absolute Truth. This is a synopsis; the Srimad-Bhagavatam goes into greater detail.

What is the characteristic of the Absolute Truth if everything emanates from it? The Srimad-Bhagavatam explains this. Consciousness must be the Absolute Truth. He is a self-sufficient individual (svarat). We acquire our consciousness and understanding by obtaining information from others, but He is considered autonomous. The Vedanta-sutra is a comprehensive summation of Vedic knowledge, and it is explained in the Srimad-Bhagavatam by the author himself. Finally, we urge individuals who are genuinely interested in Vedic information to study the Srimad-Bhagavatam and the Bhagavad-Gita for an explanation of all Vedic knowledge.

Final Note

The Vedas are thought to be the very breath of the Supreme Brahman, and its significance has been passed down through the millennia through the revelations of sages and rishis. The Lord takes on the appearance of preceptors on numerous occasions to spread this Vedic tradition, also known as Sanatana Dharma. Dakshinamurthy, a form assumed by Siva to transmit the esoteric ideas of the Vedic heritage to the sages Sanat Kumaras, the mind-born sons of Brahma, is revered as the primal Guru in the Saivite faith.

Sanatana Dharma means “righteousness” and is the foundation for all life’s material and spiritual values. From the beginning of time, it has been here and is meaningful to individuals of all ages and places. It is relevant in both the now and here since it satisfies man’s material and spiritual needs. Swami Paramatmananda emphasized in a speech that the fundamental norms of conduct must be followed regardless of gender, age, profession, or economic standing in life.

A disciplined life necessitates prioritizing all of our tasks with sufficient planning and preparation to anticipate potential barriers and prepare appropriate strategies. A sleeping lion’s mouth is said to be impenetrable to prey. All achievement necessitates tenacity. The Purana stories demonstrate the truth that what is required is sincere hard effort along with unselfish commitment. The Supreme Brahman Himself was part of the gigantic action plan and bore the brunt of the hard work by adopting the form of a tortoise to facilitate the churning of the ocean when the celestials were advised to seek the Amrita from the sea. The Vedas, particularly the Upanishads, would eventually constitute the core philosophy of Sanatan Dharma, giving believers direction and purpose in their lives. It was discovered that there was just one entity, Brahman, who created and was existence itself. Because this entity was too enormous for humans to fathom, he manifested as avatars such as Brahma (the creator), Vishnu (the preserver), Shiva (the destroyer), and a slew of other gods, all of whom were Brahman. The goal of human life was to recognize one’s higher self (the Atman) and fulfill one’s dharma (duty) with the appropriate karma (action) to break free from the cycle of rebirth and death (samsara), which was characterized by misery and loss in the physical world. Once these connections were dissolved, an individual’s Atman returned to Brahman and eternal peace.

This belief system continued to evolve until the rise of Islam in northern India, which began in the 7th century CE and grew more prominent by the 12th century CE. Hindu practices were only gradually tolerated under Islamic control. In the 18th and 20th centuries CE, British colonialism and imperialism posed considerably more danger to the Vedic worldview. The British attempted to convert the Indian people to Protestant Christianity by re-educating the population and rejecting Hinduism as a dangerous superstition. This sparked a backlash in the form of the Brahmos Movement, which was led by Ram Mohan Roy (l. 1772-1833 CE) and continued by others like Debendranath Tagore (1817-1905 CE, father of poet Rabindranath Tagore), who responded in part by reimagining their faith to distance it from the traditional form, which appeared to have been corrupted by outside influences. The Vedas’ status was lowered due to this rethinking, which included a rejection of canonical authority. The Brahmos Movement, in reality, dismissed the Vedas as superstitious foolishness and instead centered on a personal encounter with the Divine, which was eerily similar to both Protestant Christianity and the older Hindu Bhakti Movement of the Middle Ages.

Any modern Hindu sect or movement that rejects the Vedas draws its foundations from 19th- and early 20th-century CE initiatives like Brahmos. On the other hand, Orthodox Hindus continue to hold the Vedas in high respect. The works are still chanted and sung by those who see the mystery of an inexpressible truth presented without easy explanation be experienced without needing to be understood.

On the authority of the Vedas, several Hindu religions and Indian philosophies have taken opposing stances. The Vedas are classified as “orthodox” (stika) by schools of Indian philosophy that recognise their authority. Other ramaa traditions that did not view the Vedas as authoritative, such as Lokayata, Carvaka, Ajivika, Buddhism, and Jainism, are referred to as “heterodox” or “non-orthodox” (nstika) schools. Though many religious Hindus implicitly recognise the Vedas’ authority, most Indians today “give lip respect to the Veda and have no regard for the substance of the text,” and “most Indians today pay lip service to the Veda and have no regard for the contents of the text.” According to Lipner, some Hindus question the Vedas’ authority while implicitly admitting the Vedas’ significance in Hinduism’s history. The authority of the Vedas was recognised by Hindu reform movements such as Arya Samaj and Brahmo Sama, but it was challenged by Hindu modernists such as Debendranath Tagore and Keshub Chandra Sen, as well as social reformers such as B. R. Ambedkar.